Mismatched alloys are a good match for thermoelectrics

January 25, 2010

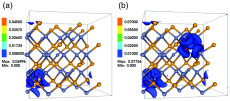

Contour plots showing electronic density of states in HMAs created from zinc selenide by the addition of (a) 3.125-percent oxygen atoms, and (b) 6.25 percent oxygen. The zinc and selenium atoms are shown in light blue and orange. Oxygen atoms (dark blue) are surrounded by high electronic density regions. Select image to enlarge. (Credit: Junqiao Wu).

Employing some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have shown that mismatched alloys are a good match for the future development of high performance thermoelectric devices. Thermoelectrics hold enormous potential for green energy production because of their ability to convert heat into electricity.

Computations performed on “Franklin,” a Cray XT4 massively parallel processing system operated by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), showed that the introduction of oxygen impurities into a unique class of semiconductors known as highly mismatched alloys (HMAs) can substantially enhance the thermoelectric performance of these materials without the customary degradation in electric conductivity.

“We are predicting a range of inexpensive, abundant, non-toxic materials in which the band structure can be widely tuned for maximal thermoelectric efficiency,” says Junqiao Wu, a physicist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a professor with UC Berkeley’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering who led this research.

“Specifically, we’ve shown that the hybridization of electronic wave functions of alloy constituents in HMAs makes it possible to enhance thermopower without much reduction of electric conductivity, which is not the case for conventional thermoelectric materials,” he says.

Collaborating with Wu on this work were Joo-Hyoung Lee and Jeffrey Grossman, both now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The team published a paper on these results in Physical Review Letters titled, “Enhancing the Thermoelectric Power Factor with Highly Mismatched Isoelectronic Doping.”

Seebeck Effect and Green Energy

In 1821, the German-Estonian physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck observed that a temperature difference between two ends of a metal bar created an electrical current in between, with the voltage being directly proportional to the temperature difference. This phenomenon became known as the Seebeck thermoelectric effect and it holds great promise for capturing and converting into electricity some of the vast amounts of heat now being lost in the turbine-driven production of electrical power. For this lost heat to be reclaimed, however, thermoelectric efficiency must be significantly improved.

“Good thermoelectric materials should have high thermopower, high electric conductivity, and low thermal conductivity,” says Wu. “Enhancement in thermoelectric performance can be achieved by reducing thermal conductivity through nanostructuring. However, increasing performance by increasing thermopower has proven difficult because an increase in thermopower has typically come at the cost of a decrease in electric conductivity.”

To get around this conundrum, Wu and his colleagues turned to HMAs, an unusual new class of materials whose development has been led by another physicist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division, Wladyslaw Walukiewicz. HMAs are formed from alloys that are highly mismatched in terms of electronegativity, which is a measurement of their ability to attract electrons. The partial replacement of anions with highly electronegative isoelectronic ions makes it possible to fabricate HMAs whose properties can be dramatically altered with only a small amount of doping. Anions are negatively charged atoms and isoelectronic ions are different elements that have identical electronic configurations.

“In HMAs, the hybridization between extended states of the majority component and localized states of the minority component results in a strong band restructuring, leading to peaks in the electronic density of states and new sub bands in the original band structure,” Wu says. “Owing to the extended states hybridized into these sub bands, high electric conductivity is largely maintained in spite of alloy scattering.”

In their theoretical work, Wu and his colleagues discovered that this type of electronic structure engineering can be greatly beneficial for thermoelectricity. Working with the semiconductor zinc selenide, they simulated the introduction of two dilute concentrations of oxygen atoms (3.125 and 6.25 percent respectively) to create model HMAs. In both cases, the oxygen impurities were shown to induce peaks in the electronic density of states above the conduction band minimum. It was also shown that charge densities near the density of state peaks were substantially attracted toward the highly electronegative oxygen atoms.

Wu and his colleagues found that for each of the simulation scenarios, the impurity-induced peaks in the electronic density of states resulted in a “sharp increase” of both thermopower and electric conductivity compared to oxygen-free zinc selenide. The increases were by factors of 30 and 180 respectively.

“Furthermore, this effect is found to be absent when the impurity electronegativity matches the host that it substitutes,” Wu says. “These results suggest that highly electronegativity-mismatched alloys can be designed for high performance thermoelectric applications.”

Next Up: Synthesizing HMAs for Testing

Wu and his research group are now working to actually synthesize HMAs for physical testing in the laboratory. In addition to capturing energy that is now being wasted, Wu believes that HMA-based thermoelectrics can also be used for solid state cooling, in which a thermoelectric device is used to cool other devices or materials.

“Thermoelectric coolers have advantages over conventional refrigeration technology in that they have no moving parts, need little maintenance, and work at a much smaller spatial scale,” Wu says.

This project was supported under Berkeley Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program.

About NERSC and Berkeley Lab

The National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility that serves as the primary high performance computing center for scientific research sponsored by the Office of Science. Located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, NERSC serves almost 10,000 scientists at national laboratories and universities researching a wide range of problems in climate, fusion energy, materials science, physics, chemistry, computational biology, and other disciplines. Berkeley Lab is a DOE national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy. »Learn more about computing sciences at Berkeley Lab.